Scientific

Discover Drawmetrics: Leading the Way in Attitude Assessment Tests and Employee Evaluation

Technology

The HRTech behind Drawmetrics initially revolved around psychometric matching of drawings and psycho-analysis, a concept somewhat reminiscent of the Rorschach Test, but distinctly different in its methodology and application. Our primary focus has always been on creating a robust attitude assessment test platform that stands out as an essential employee assessment tool.

As Generative AI has evolved over the last two years, so has our technology. We now leverage the latest outputs from Generative AI, enhancing our systems to become more robust against AI-generated resumes and minimizing any form of human bias. This ensures a fairer and more accurate assessment of candidates.

Our attitude assessment test platform is designed to be at the forefront of employee assessment tools, offering comprehensive pre-hire assessments. By incorporating Natural Language Processing (NLP), k-nearest neighbors, Graph Neural Networks, and Generative AI outputs, we automate and differentiate our reporting and analysis processes. This sophisticated technology enables us to deliver detailed insights into candidates’ personalities and potential fit for specific roles, making our personality test for employees highly reliable and effective.

We continue to invest heavily in research and development to bring you the latest advancements in machine learning and data analytics. Our commitment to innovation ensures that our applications for talent acquisition and talent management systems remain cutting-edge, providing unparalleled value to our clients.

If you’re interested in contributing to this exciting journey, reach out to explore potential opportunities with us. Together, we can shape the future of HR technology and revolutionize the way organizations assess and manage their talent. [Only shortlisted applicants will be notified]

Drawmetrics

Drawmetrics now incorporates online Doodle Drawings to measure key metrics within the HRTech recruitment and employee assessment platforms at AttituX.

Originally inspired by the work of Hermann Rorschach, the Swiss psychologist who created the inkblot test in 1921, our approach leverages the concept of interpreting “ambiguous designs” to assess an individual’s personality—a practice that dates back to the times of Leonardo da Vinci and Botticelli.

Rorschach meticulously crafted and selected ten inkblots for their diagnostic value after experimenting with several hundred. Building on these scientific principles over the past 20 years, we have reverse-engineered this concept to develop a completely different set of ten symbols, designed to assess an individual’s state of mind in a pre-employment context.

Our attitude assessment test, which is part of these symbols, has been validated using widely accepted psychometric tools, including the 16 Personality Factors, to ensure accurate and insightful personality assessments.

Let us demonstrate the scientific logic of Drawmetrics in a simple illustrations.

Look at the following symbol:

It represents, as an example, how we go about making a decisions.

We can either move forward, move backward, go left or go right. Or we can stay where we are (don’t move and don’t decide). This process outlines a cross as above.

Everyone of us go through the same logic (forward, backward, left, right or stay put) in ALL of our decision making process.

Our algorithm then analyzes, what you draw and how that relates to:

1.Money

2.Relationships

3.Work

4.Business

5.Morals

6.Conflict

7.Principles

8.Ethics

9.Personality

10.Potential Blindspots

This simple scientific logic cannot be gamed when an individual visualises this same cross in their minds, their dominant style of decision making in that specific areas are shown subconsciously without their ability to manipulate the results.

Hence the high degree of accuracy and specificity within our talent management tools and recruitment management software.

Download a copy of our Whitepaper (on our Sitemap) to understand more.

Drawmetrics Certificate of Acceptance

Drawmetrics has been officially accepted as a peer-reviewed scientific study to be published in the Journal of Behavioral Sciences (MDPI), an internationally recognized open-access journal indexed in PubMed.

The accepted manuscript, “Psychometrics of Drawmetrics: An Expressive Semantic Framework for Personality Assessment”, presents the scientific foundation, methodology, and psychometric validation behind the Drawmetrics assessment framework.

This publication marks an important milestone, reinforcing Drawmetrics’ commitment to scientific rigor, transparency, and evidence-based assessment, and positions Drawmetrics as a research-backed tool within the field of behavioral and personality sciences.

Psychometrics of Drawmetrics: An Expressive–Semantic Framework for Personality Assessment

Larry R. Price

Abstract

Background: The Big Five personality inventory provides reliable and valid measures through its lexical self-report method. Drawmetrics (DM) is an expressive-semantic personality assessment that evaluates personality attributes through graphical drawings and their corresponding linguistic terms. Methods: Linguistic terms were used to derive psychometric scores for evaluating reliability, and structural, criterion, and convergent validity relative to the Big Five model. The Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT) language model was used to process DM data for analysis. Analyses detected patterns in the data, which were then tested. The evaluation included the reliability of the α, ω, and ωₕ parameters, as well as network edge stability and consistency in centrality measurements. Results: The DM assessment achieved high internal consistency and a stable network structure. Network modularity analysis detected five domains that closely followed the Big Five personality trait structure. DM demonstrated convergent validity through high correlation coefficients, while discriminant validity established clear distinctions between DM and the Big Five. Structural validity estimates indicate that the DM domains align with the Big Five latent composites, and the criterion validity assessments confirm this alignment. Conclusion: DM demonstrated its psychometric viability by showing how people express their personality traits through nonverbal symbolic expressions.

Keywords : DM; Big Five; nonverbal assessment; computational linguistics; natural language processing; network psychometrics

Subject : Social Sciences – Behavior Sciences

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Problem

The evaluation of personality is a core component that underlies both practical psychological applications and organizational recruitment processes and leadership training programs. The Big Five model of personality has ruled organizational and personality psychology since the 1990s by establishing a cogent classification system that organizes traits into five major categories (John & Srivastava, 1999; Costa & McCrae, 1992; McCrae & John, 1992; Goldberg, 1992). The taxonomy serves as a common methodological framework by linking scientific data with common definitions of its terminology. Despite its strengths, the method is sometimes criticized for studying general language patterns rather than analyzing storytelling elements (Uher, 2013; McAdams, 1992) and for failing to provide comprehensive explanations (Block, 2010; Block, 1995). Self-report inventories require people to rely on their internal experiences and word choices instead of actual expressions for their assessment. The current study is the first in a three-part validation program designed to establish the psychometric evidence base for DM. The research aims to determine whether DM maintains the same structural pattern as the Big Five personality traits and demonstrates psychometric properties equal to or better than those of current lexical trait assessment methods. This work served as a foundation for the validity of DM as an expressive assessment framework. Four aims guided this study. The first aim required NLP and network psychometrics to assess the structural validity of DM relative to the Big Five structure using the same sample. The second aim required assessing DM reliability using conventional assessment methods and network-based evaluation approaches. Aim three involved testing factorial and criterion validity of DM. Aim four tested for convergent and discriminant validity of DM relative to the Big Five.

1.2. Conceptual Gap

To improve an organization’s success, it needs specific personality-based behavioral data that shows how employees work together, stay practical, and generate new ideas. The geometric structure of personality can be revealed through the analysis of linguistic and expressive data that provides rich information for psychometric analyses. The Big Five Inventory assesses how people describe themselves and others using verbal, self-report-based language. DM uses nonverbal and semantic production to understand personality structure, as people express their personality through their expressive–semantic manifestations in doodling and term association. DM employs personality assessment through expressive methods that function independently of language needs, introspection, and response bias. The DM approach to personality assessment has yet to be rigorously evaluated psychometrically. This study addresses this gap in research literature.

1.3. Nonverbal Testing of Personality

Psychologists have studied nonverbal and projective methods for almost 100 years to measure personality traits that standard word-based assessments cannot assess. The first tests in this field were developed by Murray (1943), who created the Thematic Apperception Test, and Cattell (1957), who designed drawing assessments. The assessment methods show promise, yet they fail to meet necessary psychometric standards because experts view them as subjective, untransparent, and non-scientific (Lilienfeld et al.,2000). The Big Five taxonomy was developed through lexical approaches (Uher, 2013; Costa & McCrae, 1992; Goldberg, 1992; McCrae & John, 1992), which established a fundamental system for personality research. DM offers a novel alternative to the lexical approach to personality assessment. During the DM assessment, participants create simple hand-drawn sketches using doodles that map to their professional and personal attributes. This mapping is then used to build an organized semantic field. The projective methods retain their expressive power through individualized meaning systems, or semantic graphs, that enable computational assessment. Personality assessment now uses new methods that move beyond traditional lexical and introspective inventory approaches to serve real-world needs. This research applied Taxonomic Graph Analysis (TGA) from Golino and Eskamp (2017) to study how DM terms related to Big Five domains and facets through network-based clustering methods. The TGA method works best for this purpose by detecting network clusters at different resolution levels from term embeddings, enabling researchers to study how clusters relate to one another. It was hypothesized that DM would discover term clusters that linked to Big Five facets and domains and those that did not exist to validate (a) the scientific merit of personality lexicon-semantic associations, (b) reveal concealed structural patterns, and (c) produce workstyle descriptions that fulfill organizational needs.

1.4. Significance of the Study

This study adds value to psychometric science by demonstrating how expressive–semantic data can be converted into quantitative measurement models. The DM system assesses personality through visual and textual relationships rather than standard word-based self-evaluation techniques. Here, I used NLP embedding techniques to transform DM semantic content into vectorized forms, thereby creating a geometric framework for assessing internal reliability and structural and criterion validity. Results of the NLP process were validated through various tests that evaluate the Big Five personality traits against the DM-transformed scale using network and latent-space alignment methods (canonical correlation, RV, Procrustes, and distance correlations). Particularly novel in this work is the use of representational measurement, network psychometrics, and natural language processing to test whether expressive–semantic structures can replicate and extend traditional lexical trait architectures. The results of this integrated approach demonstrated that DM functions as an effective personality assessment measurement tool, enabling researchers to develop new psychometric applications through its embedded models. Two new paradigms are included in this paper. First, by operating in a geometric vector space, reliability and consistency can be estimated using semantic coherence and network stability, in addition to Cronbach’s α (Cronbach, 1951) or ω (McDonald, 1999). To the best of my knowledge, this research marks the first time RMT has been integrated with network psychometrics and natural language modeling of expressive–semantic structures.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

An official employed at AttituX Ltd. Pte. used convenience sampling by sending emails to respective organization contacts to solicit volunteers to participate in a scientific study evaluating the psychometric properties of DM and benchmarking it against the Big Five Inventory. The final sample consisted of data from one hundred eighty-five (N=185) individuals who completed DM and the Big Five assessments. All participants were provided with an anonymous report for their DM and Big Five results. Respondent information was anonymous to the researchers and others involved in the study. The data collection official obtained informed consent prior to participants taking the DM and Big Five assessments. The researchers did not collect demographic information or any personal identifiers from participants to prevent exposure of their identities. Organizations included in the sample were universities, workforce and staffing companies with candidates, businesses including multi-national employees, and bosses from C-Suites, middle management, and entry-level staff. The sample included Asia Pacific (10 countries), Australia and New Zealand, Western Europe (Italy, Spain, France, and Germany), the Middle East (Saudi Arabia and the UAE), and the Americas (Canada).

2.2. Measures

DM is a nonverbal assessment that uses expressive-semantic-based methods to evaluate personality attributes through symbolic doodles that convert expressive semantics into geometric embeddings. These expressive elements are analyzed using natural language embeddings, producing structured term-based personality profiles. The DM framework incorporates conceptual components of representational measurement theory (RMT) from Suppes et al. (1959) in its measurement methodology. For example, Krantz et al. (1971) established an empirical relational structure through the expressive connections between semantic and graphical terms. The semantic embedding process converts these relationships into a vector space that preserves the structural relationships among psychological constructs via a homomorphic representation. Here, I evaluated how well the mapping system preserves the established organizational structure of personality domains through validity assessments. These analyses evaluated how well representational mapping (structural homology) matched real-world data from a pragmatic perspective. The pragmatic measurement approach enables the transformation of expressive semantic meanings into geometric representations, as described by Hand (2004) and by Golino & Christensen (2020) in network psychometrics.

When taking the DM assessment, respondents are presented with a set of figures (i.e., stimuli presented as standardized drawings). Respondents use sketches or doodles to create images from the standardized line drawings, which they then assign descriptive terms. Each figure is conceptualized as an “item” or “stimulus,” and each participant creates a doodle for ten separate line drawings, which serve as the basis for the doodling process. For each figure created, participants supply a word or phrase for their doodle that represents attributes describing either a professional orientation or a personal orientation. The object receives its name through a process that connects it to attitudinal terms established by professionals and academics who have served, or who currently serve, as subject-matter experts. Post testing, a person’s data comprises 10 professional terms and 10 personal terms from the doodle drawings. The test contains 5 foil figures that show neutral or ambiguous content to detect intentional response manipulation through their semantic variations. The system produces individual participant reports that display their personalized attitude terms, their affective-task attitude relationships, and their organizational role suitability. The test duration depends on doodling speed, and most participants complete it within 15 to 20 minutes. The creation of summary reports proceeds by processing responses and generating an attribute- or term-based inventory organized into personal and professional categories. Automated reports are immediately provided to the person assessed. The Big Five Inventory (BFI) is a self-report assessment tool that measures the Five-Factor Model of personality by evaluating Openness to Experience, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism (Kwapil, T. R., 2002). The BFI-44 inventory contains 44 short statements that respondents rate on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The International Personality Pool (IPIP-NEO 120, Johnson, 2014; Goldberg, et al., 2006) contains 120 items organized into five domains, with six facets per domain and four items per facet, for a total of 30 facets. The system provides domain-level and facet-level trait scores for assessment. The BFI lacks foil items, but some questions appear in reverse order to reduce acquiescence bias. The system produces reports through domain- and facet-score calculations and normative sample-based standardization. The final output provides T-scores and percentile ranks for each of the five domains, together with their respective facets. The IPIP-NEO 120 inventory requires 20 to 40 minutes to complete. The system produces reports instantly when it uses automated scoring keys. The five domain scales demonstrate adequate to high internal consistency reliability, with alpha values ranging from .79 to .86, while all facet scales achieve reliability coefficients above .60 (Johnson, 2014). The IPIP-NEO 120 was used in this study.

The Big Five is based on latent-variable confirmatory factor models that sometimes mask structural interdependencies among traits, facets, and behavioral indicators. Network psychometrics accounts for interdependence among behavioral indicators by using a systems-based approach. In the system approach, observed variables represent hidden traits and states, while network models show these variables as system nodes that connect through relationships (Eskamp et al., 2017). The approach reveals how personality traits form cohesive groups that link different domains while occupying central or peripheral positions within the network. Network models also enable researchers to study patterns of stability and change over time and facilitate testing network structural invariance. The properties provided in network models aid researchers in understanding how personality traits remain stable while also predicting future changes. For example, highly central traits may act as “hubs” (Costantini et al., 2015; Barabási & Albert, 1999) whose activation influences a wide range of behaviors, while peripheral traits may vary without destabilizing the system. The DM assessment uses semantic term similarity and clustering to connect individual responses to personality-related terms, yielding detailed observations of how people express their core characteristics. Here, semantic NLP methods are used to analyze DM through structural property measurement, Big Five domain and facet comparison, and the discovery of new traits that traditional trait assessments fail to detect. The Big Five is the starting point for developing an integrated method that unites traditional trait terminology with contemporary network analysis and computational text processing methods.

2.3. Data Processing

Data processing occurred after importing respondents’ data in Portable Document Format (PDF) and batch-extracting terms using Python (2023, version 3.11) scripts. Terms were captured then reviewed for accuracy using established DM criteria and, where necessary, corrected using a custom sanitizer to remove duplicates and noise (e.g., “nan,” advertising text, etc.). IPIP-NEO 120 responses were provided as portable document format (PDF), and domain and facet scores were batch-extracted using Python (2023, version 3.11) scripts written by the author. To prepare the raw data for semantic network analysis, a Python script was written to extract and clean the data (van Rossum, G., & Drake, F. L., Jr., 2009). The script extracts facet terms from DM PDFs and facet/score values from Big Five PDFs, then outputs comma-separated value (CSV) files in both wide and long formats.

2.4. Rater Agreement Analysis

Prior to network psychometric analysis, a rating-scale analysis was performed by three subject matter experts using a content rating worksheet to examine the absolute agreement of terms using syntactic and semantic rules on DM and the Big Five. Expert ratings of trait intensity served as a human check of content validity regarding the alignment produced by natural language processing. The content rating worksheet included an ordinal graded response numerical format for sematic and syntactic terminology with numerical values ranging from 1 (no match-terms are entirely unrelated), 2 (weak match-very little similarity, vague or indirect connection), 3 (moderate match-clear similarity in meaning or structure, but notable differences remain), 4 (substantial match-high degree of similarity, terms are closely aligned with minor difference), 5 (exact match-terms are identical or interchangeable in context). Rater reliability was assessed using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC; Shrout & Fleiss, 1979) based on a two-way random-effects model for absolute agreement. The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC = .88) revealed high absolute agreement among raters. Established guidelines suggest that ICC values above .75 indicate good reliability and those above .90 indicate excellent reliability (Shrout & Fleiss, 1979; Koo & Li, 2016).

2.5. Data and Network Analysis

Network analyses were conducted to evaluate the reliability, structural, and convergent validity of DM relative to the Big Five. Reliability and validity analyses were conducted using conventional and network-based psychometric techniques.

The participants recorded 20 expressive DM terms for each response (mean ≈ 20, range = 19–24), describing their personal characteristics and attitudes. The BERT model (Devlin et al., 2019) analyzed DM and Big Five terms to create high-dimensional semantic representations, which allowed the author to perform vector-based similarity assessments that demonstrated contextual comprehension. The all-MiniLM-L6-v2 Sentence Transformer (Reimers & Gurevych, 2019) produced 384-dimensional semantic representations for DM terms, enabling researchers to calculate semantic similarity using cosine distances. The embedding process for Big Five facet terms was treated the same as for DM terms to achieve measurement consistency. The resulting embeddings were aggregated into thirty DM facet-level composites corresponding to the Big Five personality domains. Big Five facet terms (n = 30) were processed using the same embedding procedure to ensure methodological equivalence. A psychometric network analysis using Taxonomic Graph Analysis (TGA) was then conducted separately for the DM and Big Five data to identify attitudinal clusters via community detection. The Louvain and hierarchical clustering methods from Blondel et al. (2008) detected attitudinal clusters while network-level metrics evaluated internal structure and cross-model alignment through centrality and bridge expected influence and modularity measurements. The network-based approach enables researchers to evaluate structural validity, convergent and discriminant validity, and criterion validity through quantitative assessments of the similarity between the DM and Big Five latent architectures. The geometric representation enabled the creation of numeric scales through cosine similarity calculations, projection methods, and regression-weighted analysis, which allowed for verification of structural validity and reliability and for assessing convergent and discriminant validity against Big Five Likert-based scores and semantic structures.

2.6. Reliability Analysis

Reliability estimation was conducted using established psychometric metrics and new semantic–geometric methods to evaluate internal consistency and structural stability. The use of a semantic-geometric approach enabled the generation of vectors, which in turn allowed the creation of a correlation matrix. The inter-item (term) correlation matrix was used to estimate domain- and facet-level reliability indices using Cronbach’s α and McDonald’s ω (total). The stability and bias of estimated values were assessed using 95% percentile bootstrap confidence intervals, based on 1,000 resampling iterations.

Next, a bifactor confirmatory factor analysis was used to test the hierarchical structure of a general factor and five group factors, each with at least 5 indicators. The assessment of internal semantic reliability used vector-based similarity metrics derived from BERT embeddings. The DM term vectors from each participant were combined to generate similarity matrices, which were used for calculating mean inter-vector coherence as a measure of semantic space consistency. In all, the three methods for evaluating reliability were: classical internal consistency assessment, bifactor modeling, and semantic–network stability analysis. Each participant’s DM term vectors were aggregated to compute pairwise cosine similarity matrices, from which mean inter-vector coherence was calculated as an estimate of internal consistency in semantic space. The network’s structural stability was assessed using a bootstrapped structure-recovery approach. Christensen et al. (2020) demonstrated that network recovery frequencies above .66 indicate reliable dimensional recovery. Network reliability indices in this study achieved parameter recovery indices exceeding 0.66. Reliability was evaluated using three methods: classical internal consistency, bifactor modeling, and semantic–network stability analysis. The R programming environment (R Core Team, 2025) served as the platform for performing all reliability assessments.

3. Results

3.1. Classical Reliability

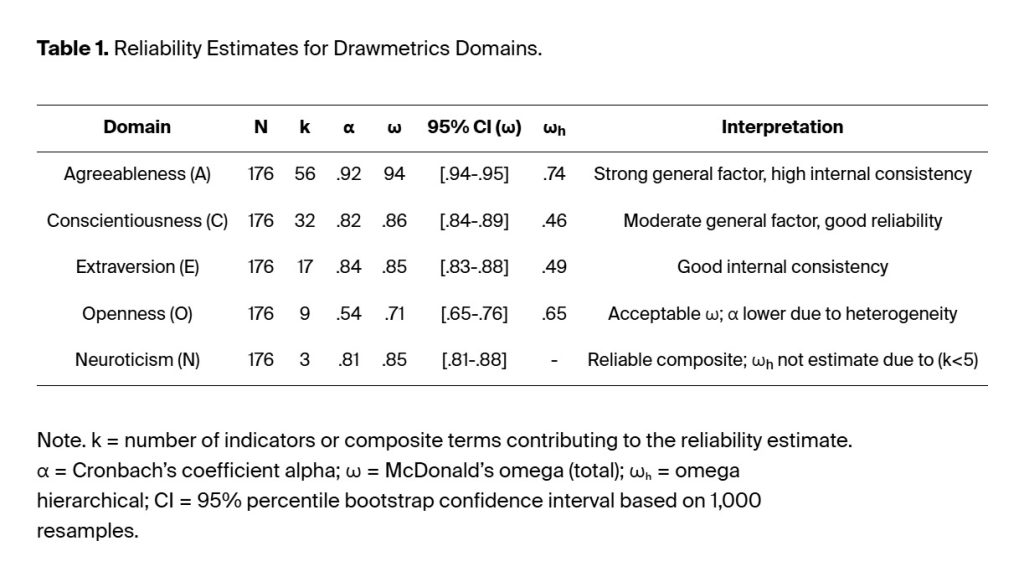

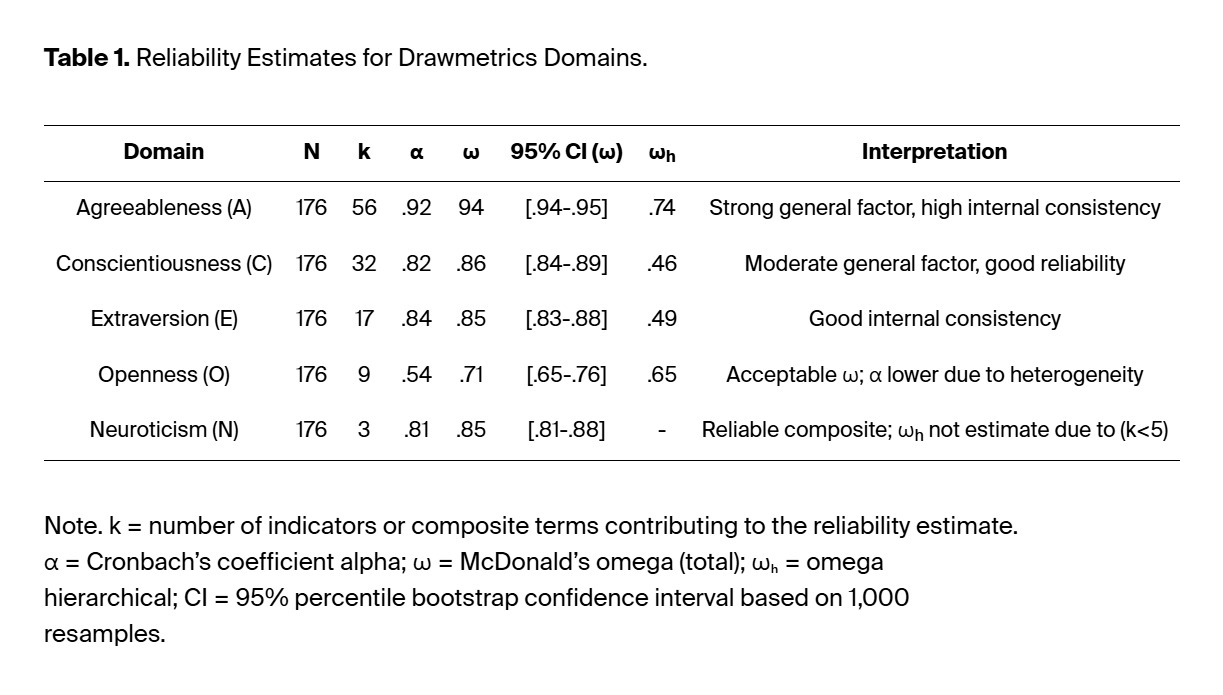

Internal consistency and general factor strength for each DM domain were assessed using Cronbach’s α, McDonald’s ω, and Hierarchical ωₕ (Zinbarg, 2006). These indices were derived from the bifactor model results. The reliability estimates appear in Table 1.

Reliability estimates were good to excellent, with α values between .81 and .92 and ω values between .71 and .94. The reliability of Openness (α = .54) was lower than that of the other domains. The hierarchical omega (ωₕ) values indicated that most domains contained substantial general factor components, ranging from .46 to .74. This range represents a ωh variance of .21-.55 in the general factor after accounting for group- or individual-level domain factors. The hierarchical omega (ωₕ) values indicate that Conscientiousness and Extraversion were largely multidimensional. Agreeableness and Openness include a general factor, with domains making unique contributions. The internal consistency of Agreeableness and Conscientiousness was highest due to their general factor loadings of (ωₕ = .74 and .52, respectively). Their alpha values exceeded .84 and their omega values exceeded .85. Extraversion showed good reliability with α = .84 and ω = .85. and ωₕ = .49. The three Neuroticism indicators demonstrated high reliability even though they consisted of only three items (k = 3; α = .81, ω = .85). The Openness scale yielded an α coefficient of .54 and ω coefficient of .71. Omega hierarchical (ωₕ) reached .65 with multidimensionality across multiple dimensions. The Bootstrap confidence intervals (95 %) confirmed the precision of these estimates through their standard errors, which ranged from ±.02 to ±.04.

The results confirmed that the internal organization of DM domains was preserved, with a moderate to strong general factor and good to excellent domain Omega (ω) reliability (i.e., .71 – .94).

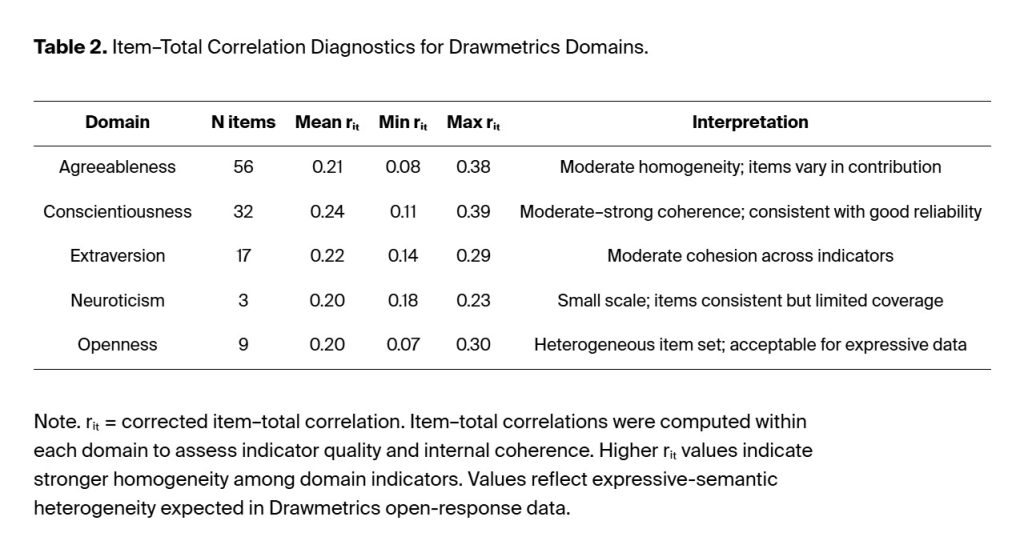

3.2. Item-Level Analysis

Evaluation of the internal structure also included item-level diagnostic tests across all domains of the DM assessment. The corrected item–total correlations (rᵢₜ) ranged from .07 to .39 across domains, while the mean values ranged from .20 to .24, indicating moderate internal homogeneity (Price, 2016). The range of item–total correlations is likely due to the open-ended response format of DM terms. The removal of any single item from the assessment produced a change in α and ω values of less than 0.02, confirming that domain items remain coherent, as indicated by the Table 1 reliability results. The results from item analysis appear in Table 2.

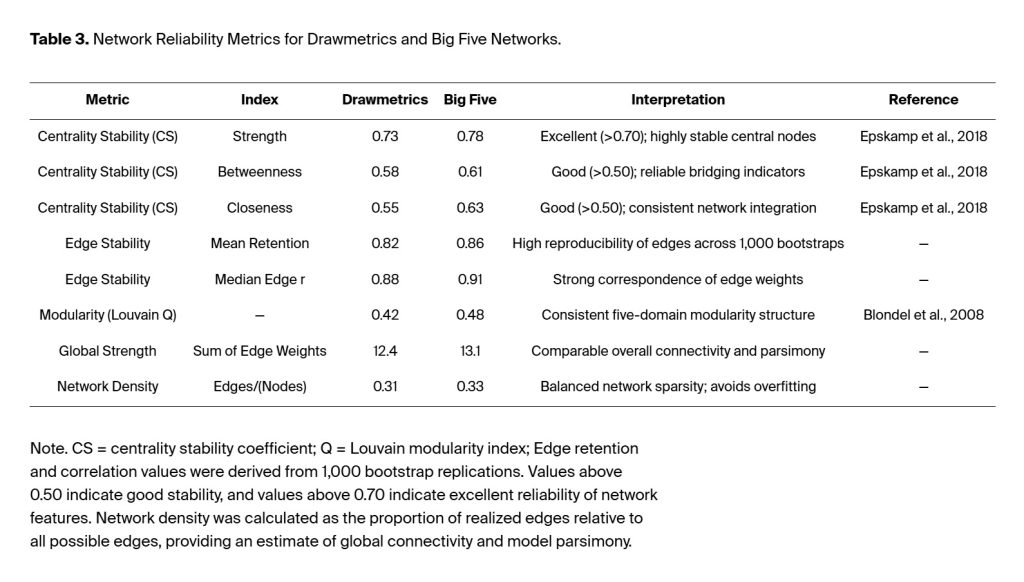

3.3. Network Reliability

Network reliability analysis used a bootstrap-based resampling method to examine how well the Big Five structure of DM’s semantic–attitudinal structure exhibited stability and consistency. The analysis used case-dropping bootstrap sampling to calculate centrality stability coefficients (CS) (Epskamp et al. 2018; Christensen and Golino, 2021). The CS assesses the stability of network centrality results after bootstrap procedures remove cases. It represents the most significant proportion of participants that can be removed while maintaining a correlation of at least .70 between the original and bootstrapped centrality values. According to Christensen and Golino (2021), network stability remains stable at .50 and above but becomes unstable when values fall below .25. Edge-weight bootstrapping was used to assess the frequency and magnitude consistency of pairwise connections across 1,000 network replications. Network modularity and community structure were examined using the Louvain clustering algorithm (Blondel et al., 2008) to determine whether DM produced stable personality domains that correspond to the Big Five personality traits.

The DM centrality stability coefficients showed high reliability through all indices, with CS (strength) at 0.73, CS (betweenness) at 0.58, and CS (closeness) at 0.55. The Big Five network showed similar results with stability coefficients of 0.78, 0.61, and 0.63. The stability of network measures reaches good levels at 0.50 and excellent levels at 0.70 and above. The edge stability analyses produced identical results because the mean edge retention frequencies were 0.82 (DM) and 0.86 (Big Five), and the median bootstrapped edge-weight correlations were r = .88 and r = .91, respectively (not shown in Table 3 ). The networks maintained stable community organization, as indicated by modularity coefficient analysis (Q_DM = 0.42; Q_B5 = 0.48), which identified five main clusters, with edge weights of 0.37 (DM) and 0.41 (B5) within each cluster. The two models displayed identical global strength indices (12.4 vs. 13.1) and densities between .31 and .33, indicating equal network connectivity and model simplicity.

The findings show that the network system functions with high reliability, representing a contemporary version of internal consistency measurement in traditional psychometric assessment. The DM semantic network shows stability through multiple resampling tests, which produce identical edge patterns and maintain domain separation and Big Five-related centrality patterns. DM maintains a reliable personality structure that emerges from expressive-semantic data, and network analysis confirms its measurement properties.

3.4. Validity Analyses

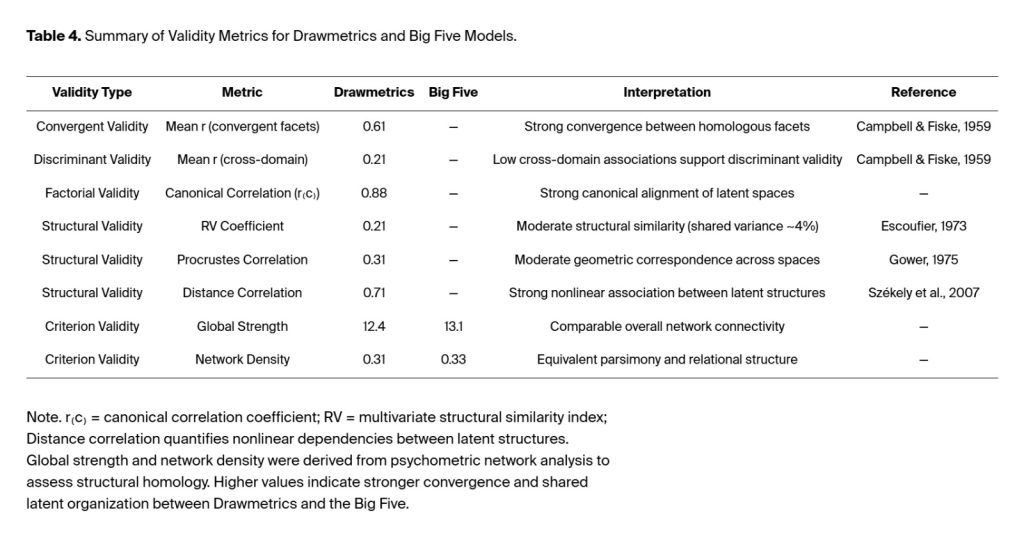

Validity tests were conducted to verify that the expressive–semantic structures from DM align with the established latent personality structure of the Big Five. The study evaluated Big Five domain associations with DM at the facet level to determine convergent and discriminant validity. The analyses included using TGA, EGA, canonical correlation, RV, Procrustes, and distance correlation analyses to evaluate both factorial and structural validity. Global network metrics were used to assess criterion validity by comparing the two networks’ performance.

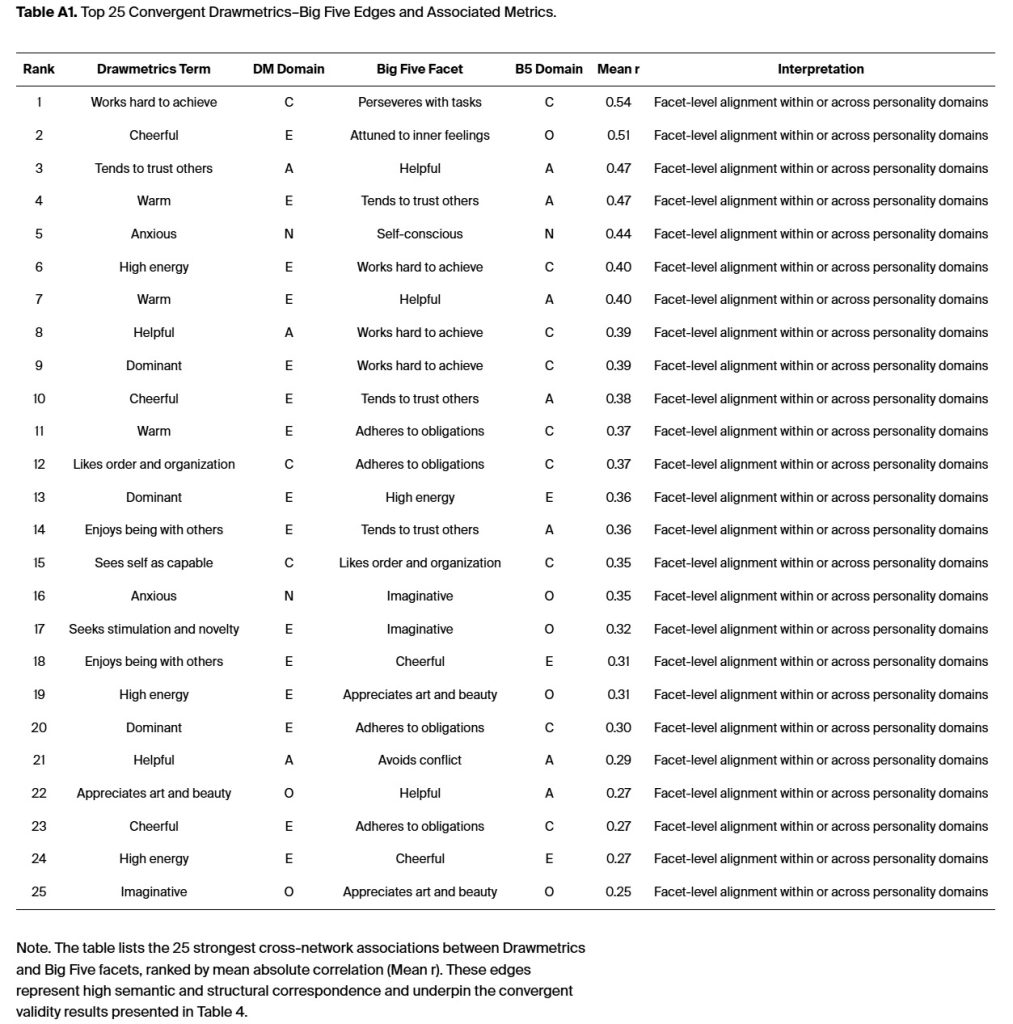

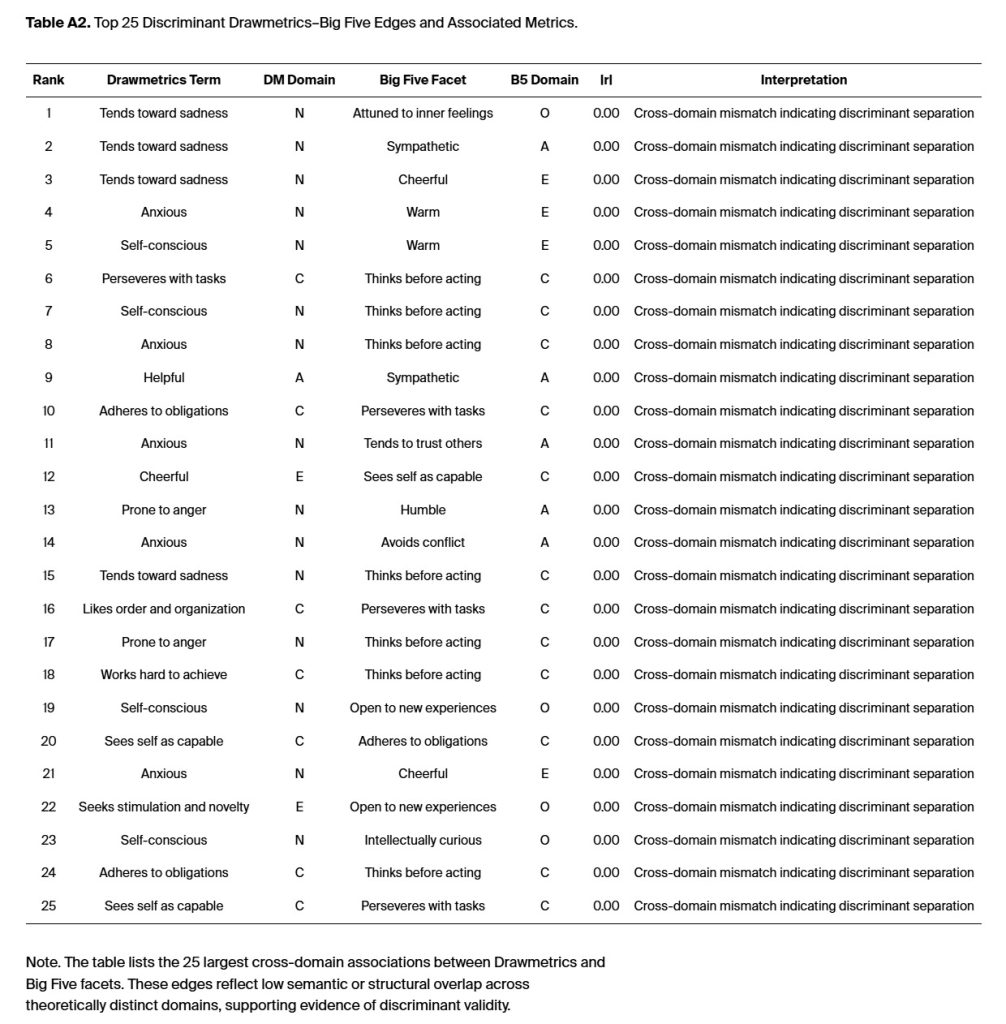

3.4.1. Convergent and Discriminant Validity

The evaluation of convergent and discriminant validity required estimating DM measurement relationships with Big Five facets through various psychometric and geometric assessment methods. The analysis included the complete set of validity metrics, which were collected from the entire network. The analysis of 30 matched facets yielded 435 potential correlations at the individual level. The convergent edges between models showed a mean correlation of r = .61, which fulfills the conventional psychometric criteria for strong trait-level congruence (Campbell & Fiske, 1959). The analysis showed that Openness (r̄ ≈ .70), Conscientiousness (r̄ ≈ .64), and Agreeableness (r̄ ≈ .59) had the strongest convergence. Different domains showed weak connections (r̄ = .21, range = .05–.34), while the average absolute difference between domains was |Δr| = .26. These results demonstrate that DM maintains separate construct domains while also aligning with Big Five domains. The study used all 435 DM and Big Five correlations to calculate the mean values which amount to r̄ = .61 for convergent and r̄ = .21 for discriminant. The top 25 illustrative edge pairs from Appendix A Table A1 and Table A2 provide a reference for interpretation. The mean values (r̄ = .61) for convergent and (r̄ = .21) for discriminant are from all 435 DM and Big Five correlations.

3.4.2. Structural and Factorial Validity

The Taxonomic Graph Analysis (TGA) together with the Louvain community detection method showed that the data were organized into five domains, which followed the Big Five theoretical framework (Q_DM = 0.42; Q_B5 = 0.48). Analyses included using Exploratory Graph Analysis (EGA) and Bayesian Gaussian Graphical Models (BGGM; Williams, 2020) to confirm that the model produced reliable dimensional results. Factorial validity was verified through its high canonical correlation between DM and Big Five composite variables (r₍c₎ = .88) showing that expressive–semantic embeddings maintained the fundamental structure of personality traits. The analysis produced coefficients with moderate to strong geometric agreement. The RV coefficients measured .21, while Procrustes (Hurley & Cattell, 1962) correlation reached .31, and distance correlation reached .71. The study established that latent spaces show partial homology because their intricate connection patterns share common elements. The RV coefficient (Abdi, 2007; Robert & Escoufier, 1976) served as a multivariate version of the squared Pearson correlation to measure the total structural alignment between two multivariate data sets, which included the DM and Big Five facet configurations. The geometric correspondence between two matrices becomes more similar as the value approaches 1, while it becomes completely unstructured at 0.

3.4.3. Criterion and Structural–Functional Validity

The global network metrics showed that DM and Big Five architecture shared similar structural patterns. The two models demonstrated equivalent strength (DM = 12.4; B5 = 13.1) and network density (0.31 vs. 0.33), which produced identical model complexity and relationship organization. The modular design and network-bridge connections between systems display uniform patterns that confirm that DM’s expressive–semantic mappings represent genuine psychological distinctions rather than following linguistic patterns. The results confirm that DM demonstrates both convergent and discriminant validity, as well as structural and factorial validity. The Big Five personality traits follow an expressive–semantic model that explains their organization and offers fresh perspectives on nonverbal and attitudinal expressions. The analysis of DM through canonical, geometric, and network-based methods shows that the model maintains psychometric stability while showing structural patterns that align with the Big Five model. DM detects most hidden elements that traditional self-report surveys indirectly measure, as evidenced by its high canonical correlation (r₍c₎ = .88) and distance correlation (.71). The model shows both strong and weak relationships with the original data, as its Procrustes and RV coefficients range from 0.5 to 0.7.

Table 4 illustrates the pattern of cross-network associations of the convergent validity estimates. The table presents a summary of DM validity indices that compare the Big Five personality traits through both correlation-based and network-level metrics.

The research provides supporting evidence for current personality theories through experimental methods while developing new theoretical models about how people express their attitudes across different situations. The two networks demonstrate their structural and functional validity by preserving their five-domain modularity and maintaining stable edge configurations and equivalent global strength. A summary of the strongest convergent and discriminant edges (top 25 facet-level DM–Big Five linkages) and associated metrics is provided in Appendix A (Table A1 and Table A2).

4. Discussion

4.1. Theoretical Contributions

The research confirms that DM is the first standardized personality assessment tool to use expressive-semantic methods to measure personality traits. The research combined natural language embedding techniques with network psychometric methods and canonical correlation analysis to prove DM assessments follow the structural design and theoretical value of conventional lexical assessment tools.

The analysis established convergent validity through findings showing that DM measures were strongly correlated with Big Five domains at the facet level (r̄ = .61). The expressive semantic representations in DM assessments preserve the same personality structure that self-report assessments like the Big Five use to measure personality traits. The fundamental word-matching system in DM terms expands into a high-dimensional space that maintains its hidden Big Five organizational structure. The low inter-domain correlations (r̄ = .21) confirmed discriminant validity because DM maintained separate constructs. The results show that expressive–semantic data yields identical psychometric relationships to those obtained with established methods while delivering results that are equal to or more precise.

DM scores remained highly stable throughout the assessment process. The internal consistency of all domains achieved acceptable to high levels, as indicated by classical estimates using Cronbach’s α and McDonald’s ω. The network-based recovery analysis produced stable results because all bootstrapped tests showed edge recovery rates above 0.66. The semantic embedding method uses graph-based metrics for aggregation to produce reliable constructs without needing traditional Likert rating systems. The method uses semantic coherence and network recovery to create a novel method for evaluating the reliability of expressive data.

The results provide validity evidence for DM through Big Five Trait Topology alignment and structural validity tests, which preserve its unique expression patterns. The Canonical correlation and Procrustes analyses produced similar results, but distance correlation and RV coefficients identified that the shared variance resulted from actual structural alignment rather than random similarities. The canonical and geometric indices of criterion validity indicate that DM yields predictive validity that equals or exceeds that of traditional inventory assessments, especially for the Conscientiousness and Openness traits that match expressive–cognitive characteristics.

The measurement-theoretic framework of DM creates a semantic expression-personality construct mapping that aligns with Hand’s (2020) pragmatic measurement theory and representational measurement theory (Suppes et al.,1959). The geometric–semantic mapping allows researchers to extract reliable and valid measurements from language data through a homomorphism that links expressive meaning to trait structure.

4.2. Expressive versus Lexical Models of Personality: Conceptual Integration

The Big Five personality model and other traditional personality models derive from the lexical tradition, which states that social characteristics exist in natural language and can be discovered through factor analysis of trait-descriptive adjectives (Goldberg, 1990; John et al., 1988). People use the Big Five framework to describe themselves with words that do not always reflect their actual behavior or physical appearance. DM shows personality through vector-based embeddings that extract attitudinal meaning from doodle-based representations, their corresponding descriptors, and nonverbal and semantic outputs. The expressive–semantic foundation studies how people develop their personal meaning systems through geometric patterns that exceed traditional lexical self-report assessment methods. The current research shows that DM upholds the Big Five structure while revealing additional expressive information that standard language-based assessments fail to measure. The current research supports a new assessment system that combines lexical and expressive evaluation through self-description and expressive production to study personality. DM unites lexical traits with attitudinal meaning to establish a single psychometric framework that connects language to symbolism and behavioral expressions for personality assessment.

4.3. Applied Contributions

The research develops innovative personality assessment techniques by creating and validating DM as an expressive assessment tool that offers an alternative to traditional self-report questionnaires. The DM system uses nonverbal and semantic signals to function well in situations where self-report questionnaires lose effectiveness due to language barriers, cultural differences, and deliberate deception. DM provides its greatest value by helping organizations select candidates and lead teams through expressive behavioral assessment, which reveals motivational and attitudinal patterns that lexical self-descriptions cannot detect. The system enables automated, scalable scoring through NLP and network analysis, which evaluates semantic and geometric consistency in expressive responses to support high-volume or remote locations. The Big Five framework maintains its interpretive continuity because DM established the structural match, demonstrating how adaptability, creativity, and interpersonal skills manifest in behavioral actions. The assessment system of DM stands out because it combines psychological measurement approaches with data science and organizational deployment, leveraging connections between expressive assessment and digital and cross-cultural human capital management systems.

4.4. Limitations and Future Directions

This study has several limitations to acknowledge. The study used a convenience sampling method, which brought together participants from various locations with different professional backgrounds, which might influence their word interpretation. A larger sample is recommended in future studies on DM to provide sufficient statistical power for more advanced analyses. The study conducted cross-validation on a single dataset at a single point in time; however, a longitudinal study will evaluate how the DM assessment maintains performance stability over time. The scalability of semantic embeddings poses challenges for researchers, who need specialized methods to extract psychological features from high-dimensional similarity matrices. Research on DM should include additional behavioral data collection and cultural diversity studies. The DM validation program will conduct two additional assessment phases to evaluate (a) criterion validity through predictive models for occupational and interpersonal results and (b) temporal stability through repeated-measures and cross-sample replication. The research will determine whether DM serves as a viable alternative to personality assessment or maintains its current role as an additional assessment tool.

5. Conclusions

DM demonstrates reliable and valid expressive measurement of personality, showing strong structural correspondence and concurrent criterion validity with the Big Five, establishing a foundation for predictive and longitudinal validation.

Funding

This research was funded by AttituX Ltd. Pte. in Singapore. The funding organization supported data collection and infrastructure for the DM assessment platform but had no role in study design, data analysis, interpretation, or the decision to publish the results.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Institutional review board (IRB) approval was not required for this research because all participant data were collected anonymously, and no identifying information was recorded. The study met the criteria for exemption from human subjects review under ethical standards for minimal-risk research. All procedures complied with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Participation in the DM study was entirely voluntary and anonymous. Participants were informed that their responses would be used for research purposes only and that no identifying information would be collected or stored. They were advised that they could discontinue participation at any time without penalty. Proceeding with the assessment constituted informed consent.

Data Availability Statement

The deidentified DM and Big Five datasets, as well as the analytic code used for this research, are proprietary to AttituX Ltd. Pte. and are not available for public access or external sharing. Results were derived from using internal analytic infrastructure in compliance with organizational data governance policies.

Acknowledgments

Portions of the Python programming and analytic documentation were prepared with assistance from ChatGPT (GPT-5), a large language model developed by OpenAI (2025). The author reviewed and verified all generated content for accuracy, methodological correctness, and consistency with the study’s empirical results. Limited assistance from an AI language model (ChatGPT, OpenAI) was used during early drafts to enhance readability and streamline expression. All substantive writing, data interpretation, and revisions were completed and validated by the author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author serves as an independent consultant for AttituX Ltd. Pte., which provided funding to the author for this research. The author is not an employee or owner of AttituX Ltd. Pte. This study was conducted independently of the author’s faculty responsibilities at The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio. The university was not involved in the study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, or the decision to publish the results. The author declares no other commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DM | DM |

| BERT | Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers |

| BGGM | Bayesian Gaussian Graphical Model |

| BF | Big Five |

| BFI | Big Five Inventory |

| r(c) | canonical correlation |

| EGA | Exploratory Graph Analysis |

| NLP | Natural Language Processing |

| TGA | Taxonomic Graph Analysis |

| r̄ | discriminant separations expressed as an average correlation |

| α | coefficient Alpha |

| ω | coefficient Omega |

| ωₕ | coefficient Omega hierarchical |

| CS | coefficient of stability in network psychometrics |

| Q | Louvain modularity index |

| r | correlation coefficient |

Appendix A

Appendix B

References

Abdi, H. (2007). RV coefficient and congruence coefficient. In N. J. Salkind (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Measurement and Statistics (Vol. 3, pp. 849–853). SAGE Publications.

Barabási, A.-L., & Albert, R. (1999). Emergence of scaling in random networks. Science, 286(5439), 509–512. [CrossRef]

Block, J. (1995). A contrarian view of the five-factor approach to personality description. Psychological Bulletin, 117(2), 187–215. [CrossRef]

Block, J. (2010). The five-factor framing of personality and beyond: Some ruminations. Psychological Inquiry, 21(1), 2–25.

Blondel, V. D., Guillaume, J.-L., Lambiotte, R., & Lefebvre, E. (2008). Fast unfolding of communities in large networks. Journal of Statistical Mechanics: Theory and Experiment, 2008(10), P10008. [CrossRef]

Campbell, D. T., & Fiske, D. W. (1959). Convergent and discriminant validation by the multitrait–multimethod matrix. Psychological Bulletin, 56(2), 81–105. [CrossRef]

Cattell, R. B. (1957). Personality and Motivation: Structure and Measurement. New York: World Book Company.

Costantini, G., Richetin, J., Preti, E., Casini, E., Epskamp, S., & Perugini, M. (2015). Stability and variability of personality networks: A tutorial on recent developments in network psychometrics.

Costa, P. T. Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1992). Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R) and NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI) professional manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Christensen, A. P., & Golino, H. (2021). Estimating the Stability of Psychological Dimensions via Bootstrap Exploratory Graph Analysis: A Monte Carlo Simulation and Tutorial. Psych, 3(3), 479–500. [CrossRef]

Christensen, A. P., Garrido, L. E., & Golino, H. (2020). A psychometric network perspective on the validity and validation of personality trait questionnaires. European Journal of Personality, 34, 1095–1108.

Cronbach, L. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika, 16(3), 297–334. [CrossRef]

Devlin, J., Chang, M.-W., Lee, K., & Toutanova, K. (2019). BERT: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, 4171–4186. [CrossRef]

Epskamp, S.; Maris, G. K. J.; Waldorp, L. J.; & Borsboom, D. (2018). “An introduction to network psychometrics: Relating Ising network models to item-response theory models”. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 53(1), 15-35.

Epskamp, S., Rhemtulla, M., & Borsboom, D. (2017). Generalized Network Psychometrics: Combining Network and Latent Variable Models. Psychometrika, 82(4), 904-927.

Goldberg, L. R., Johnson, J. A., Eber, H. W., Hogan, R., Ashton, M. C., Cloninger, C. R., & Gough, H. G. (2006). The International Personality Item Pool and the future of public-domain personality measures. Journal of Research in Personality, 40(1), 84–96. [CrossRef]

Goldberg, L. R. (1992). The development of markers for the Big-Five factor structure. Psychological Assessment, 4(1), 26–42. [CrossRef]

Golino, H. F., & Epskamp, S. (2017). Exploratory graph analysis: A new approach for estimating the number of dimensions in psychological research. Psychological Methods.

Golino, H. F., Christensen, A. P., Moulder, R., Kim, S., Boker, S. M., & McNally, R. J. (2020). Modeling psychological data as networks using Exploratory Graph Analysis: The R package EGAnet. Psychological Methods, 25(4), 567–588. [CrossRef]

Hand, D. J. (2004). Measurement Theory and Practice: The World Through Quantification. John Wiley & Sons Ltd., Chichester, West Sussex, United Kingdom.

Hurley, J. R., & Cattell, R. B. (1962). The Procrustes program: Producing direct rotation to test a hypothesized factor structure. Behavioural Science, 7(3), 258-262.

John, O. P., & Srivastava, S. (1999). The Big Five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and theoretical perspectives. In L. A. Pervin & O. P. John (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (2nd ed., pp. 102–138). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

John, O. P., Angleitner, A., & Ostendorf, F. (1988). The lexical approach to personality: A historical review of trait taxonomic research. European Journal of Personality, 2(3), 171–203. [CrossRef]

Johnson, J. A. (2014). Measuring thirty facets of the Five Factor Model with a 120-item public domain inventory: Development of the IPIP-NEO-120. Journal of Research in Personality, 51, 78–89. [CrossRef]

Koo, T. K., & Li, M. Y. (2016). A guideline for selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. Journal of Chiropractic Medicine, 15(2), 155–163. [CrossRef]

Krantz, D. H., Luce, R. D., Suppes, P., & Tversky, A. (1971). Foundations of Measurement: Vol. I. Additive and polynomial representations. Academic Press.

Kwapil, T. R. (2002). The five-factor personality structure of dissociative experiences. [CrossRef]

Lilienfeld, S. O., Wood, J. M., & Garb, H. N. (2000). The scientific status of projective techniques. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 1(2), 27–66. [CrossRef]

McAdams, D. P. (1992). The five-factor model in personality: A critical appraisal. Journal of Personality, 60(2), 329–361.

McCrae, R. R., & John, O. P. (1992). An introduction to the five-factor model and its applications. Journal of Personality, 60(2), 175–215. [CrossRef]

McDonald, R. P. (1999). Test theory: A unified treatment. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

McKinney, W. (2010). Data structures for statistical computing in Python. In S. van der Walt & J. Millman (Eds.), Proceedings of the 9th Python in Science Conference (pp. 51–56). [CrossRef]

Murray, H. A. (1943). Thematic Apperception Test manual. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Newman, M. E. J. (2006). Modularity and community structure in networks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 103(23), 8577–8582. [CrossRef]

OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT (GPT-5) [Large language model]. https://chat.openai.com.

Pedregosa, F., Varoquaux, G., Gramfort, A., Michel, V., Thirion, B., Grisel, O., Blondel, M., Prettenhofer, P., Weiss, R., Dubourg, V., Vanderplas, J., Passos, A., Cournapeau, D., Brucher, M., Perrot, M., & Duchesnay, É. (2011). Scikit-learn: Machine learning in Python. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 12, 2825–2830.

Price, L. R. (2016). Psychometric Methods: Theory into Practice. New York: Guilford Publications.

Python Software Foundation. (2023, October). Python (Version 3.11) [Computer software]. https://www.python.org.

R Core Team. (2025). R: A language and environment for statistical computing [Computer software]. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org.

Reimers, N., & Gurevych, I. (2019). Sentence-BERT: Sentence embeddings using Siamese BERT-networks. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (pp. 3982–3992). Association for Computational Linguistics. [CrossRef]

Robert, P., & Escoufier, Y. (1976). A unifying tool for linear multivariate statistical methods: The RV-coefficient. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series C (Applied Statistics), 25(3), 257–265. [CrossRef]

Shrout, P. E., & Fleiss, J. L. (1979). Intraclass correlations: Uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychological Bulletin, 86(2), 420–428. [CrossRef]

Suppes, P., Krantz, D. H., Luce, R. D., & Tversky, A. (1959). Foundations of Measurement: Vol. I. Additive and polynomial representations. Academic Press.

Uher, J. (2013). Comparative Differential and Personality Psychology, Freie Universität Berlin, Habelschwerdter Allee 45, 14195 Berlin, Germany.

Van Rossum, G., & Drake, F. L., Jr. (2009). Python 3 Reference Manual. CreateSpace.

Williams, D. R. (2020). BGGM: Bayesian Gaussian Graphical Models in R. Journal of Open Source Software, 5(51), 2111. [CrossRef]

Zinbarg, R. E., Revelle, W., Yovel, I., & Li, W. (2005). Cronbach’s α, Revelle’s β, and McDonald’s ωH: Their relations with each other and two alternative conceptualizations of reliability. Psychometrika, 70(1), 123–133.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

Copyright: This open access article is published under a Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 license, which permit the free download, distribution, and reuse, provided that the author and preprint are cited in any reuse.

Drawmetrics Executive Summary

Scientific Report